23 February 2017. Located on the lee side of the Santa Cruz Mountains just below their crest, the wine estate that Thomas Fogarty established in 1979 has persisted, and is in some ways little changed, across nearly four decades. It remains family owned and run, with Fogarty’s son Thomas Jr. now in charge. Fewer than ten percent of the land surface is built or planted to vines; the balance has been left deliberately undeveloped, and the entire property is protected in a land trust. Its views east and south, which extend across the Stanford University campus and Palo Alto to the east and south shores of San Francisco Bay, remain uncompromised. Only one of its vineyards – a two-acre knoll adjacent to the winery buildings, planted in 1980 and called Windy Hall — has been replanted. The rest of the original vines – mostly chardonnay and pinot noir with a small stand of nebbiolo — soldier on. Michael Martella, the legendary winemaker Fogarty-père engaged in 1980 to help him develop the estate, made every vintage here until 2012 and remains somehow omnipresent, even though he now devotes the lion’s share of time to a brand of his own. (Separately, Fogarty has developed a second winegrowing location on the west side of Skyline Boulevard, facing southwest, where Bordeaux varieties are grown for a second label, Lexington.)

The continuity masks real and consequential evolution, however. A January 2017 tasting of Fogarty’s 2013 pinots, contrasted substantially – even dramatically – with a similar tasting of the 2004 vintage done in 2008 to inform Pacific Pinot Noir: A Comprehensive Winery Guide for Consumers and Connoisseurs (University of California Press, 2008). The 2004 pinots were uniformly dark, large-framed and fruit-driven, and exceeded 14°. My notes speak of “black fruit,” “strong structure,” “muscle” and “omnipresent tannin,” and suggest that several years of bottle age might help to tame their brawn. The 2013s represent a polar contrast with this picture. The 2013s are pretty, bright, elegant treble-clef wines. They are also tightly-knit, texturally engaging, sometimes savory, sometimes spicy and often red-fruited. They are a great showcase for the estate’s kaleidoscopically different terroirs. And their alcoholic strength stands almost two degrees lower on average than in 2004. The 2013s are, in a word, beautiful. I asked Nathan Kandler, the Michigan-raised and Fresno-trained winemaker who succeeded Martella as winemaker in 2013 after nine years’ experience as his associate what had happened.

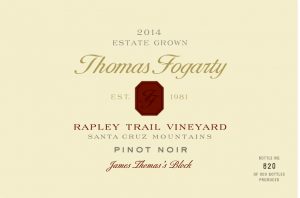

The answer, according to Kandler, begins in the vineyard. True that the Fogarty pinot program still depends on the same vines used in and before 2004, save for Windy Hill, which was taken out of production for replanting from 2011 to 2014. But viticulture across the estate has changed in small and incremental but ultimately revolutionary ways in the interim. “An estate [like Fogarty] that is spread out over a large surface makes it easy to get stuck in the cellar,” he explains. “Now we deliberately spend a lot more time outside and “pay more attention now to what we are doing there.” He points especially to soil health, and to the improvement of “diversity of life” in the soil. A legume-rich cover crop is seeded after harvest and tilled into the soil the following spring, mitigating erosion during the rainy season and increasing available nitrogen thereafter, helping to improve the “diversity of life in the soil.” Chemical herbicides have been abandoned — along with most insecticides, fungicides and chemical fertilizers. Farming in most vintages now meets most requirements for organic farming, though the vineyard is not certified. Good vine balance (technically a relationship between fruit weight and brush weight) is now a lodestone here, with shorter pruning now preferred. “In the mid-2000s,” Kandler observes, “some of our vines looked their age; now they are visibly healthier.” Healthier and better-balanced vines have also given fruit that is flavor-ripe with less sugar. To help demonstrate what has happened Kandler shared data on pinot grapes from one of the estate’s vineyards, called Rapley Trail. From 2004 to 2007, the average Brix at picking in this vineyard was 26.4 (=16.1° of potential alcohol), giving an average finished alcohol in these years of 14.3°; from 2013 to 2016 the analogous numbers were just 22.9 Brix (=13.6°) and 12.9°!

From 2004 to 2013 there were also important changes in the cellar. A period of experimentation with stem inclusion has led to the routine use of between ten and thirty percent of whole clusters for most wines in most vintages. Fermentations, which were routinely inoculated in and before 2004, now typically rely on naturally occurring yeasts. Cooperage has also changed from a wide mix of coopers, including some with notoriously flavor-forward styles like François Frères, to exclusive use of Sirugue, usually coopered from Châtillon oak, which has an enviable reputation for subtlety. At least as consequential was the choice, made incrementally over the aforementioned period, to support multiple block-designated wines. Before 2004, Fogarty made Reserve pinots, and a Santa Cruz Mountains blend that relied in part on purchased fruit, but no block designates. The latter practice began with Rapley Trail and Rapley Trail Block B bottlings in 2004. Razorback, a 1986 planting of Swan and Dijon selections and the estate’s lowest elevation vineyard at ca. 1300 feet, followed in 2011; Will’s Cabin Vineyard, a north-facing site at 2400’, planted to Mount Eden, Swan and Mariafeld selections, was first made in 2012. Windy Hill, back in production after replanting, debuted as a block-designate in 2014. My notes (from January 2017) show that Rapley Trail remains the most hedonistic of the block designates, relatively rich, dark, intense, and spicy, but in 2013 these signature properties had been wrapped into a stylish and elegant package. Will’s Ranch, reflecting the cool breed of a high-elevation site, was tightly-knit with gentle grip on the finish, but pretty and bright a mid-palate. Razorback, a lower elevation site where marine sediments and old volcanic materials predominate, was my personal favorite: very high-toned, red-fruited, tightly-knit and savory with resinous herbs, and irresistibly delicious.

It has probably been helpful that the winemaking team also makes three vineyard-designated pinots from purchased grapes, and that the Santa Cruz Mountains blend now relies preponderantly on non-estate fruit. The blend, the only one of the Fogarty pinots that is bottled before the following vintage, is all about red berries and dusty earth, with a nice accent of juniper berry; an absolutely perfect wine for weekday evenings and by-the-glass pours. La Vida Bella Vineyard, which sits above the fog line on the Aptos side of the appellation in sandy loam soils, showed as a bright, spicy wine with a silky texture and red berry flavors. Mindego Ridge Vineyard – Ehren Jordan is the winemaker for Mindego Ridge’s own label — is a 2009 planting in shale-dominated soils that gives a fleshy, saturated wine driven by fairly dark fruit.

The Santa Cruz Mountains have matured as a winegrowing region over the last decade. The region now boasts considerable professional winemaking talent. New vineyards have been planted in all corner of the AVA, some challenging Mother Nature for sites that as qualitatively promising as they are hard and risky to farm. Legendary Silicon Valley fortunes have been indispensible to some of these. Bottom Line however is that there is now an impressive list of benchmark pinot noirs from this area. Among the near pioneers that have persisted, Fogarty stands out as a twice-made success: the “new” pinots from this now “old” site are as exciting as those from any of the newly-planted vineyards and newly-minted brands.