Gernot Kollmann visited the west coast of the United States a few months back, his stops in Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles better measured in hours than in days, hurrying home in time to pick Riesling in the Mosel. Kollman is the man in charge at Weingut Immich-Batterieberg, here to visit accounts with his Bay Area distributor, Keven Clancy of Farm Wine Imports. Dinner with them and Gilian Handelman (Director of Education and Communications at Jackson Family Wines and Keven’s wife) at Aster, a Michelin-starred establishment in San Francisco’s Mission district, was a great and welcome opportunity to catch up on recent editions of the property’s single-vineyard Rieslings. All of these are sourced within a stone’s throw of Enkirch, a town downstream of Traben and Trarbach. (Coincidentally, Enkirch is also about eleven kilometers northwest of Hahn, Frankfurt’s “second” airport, a well-kept secret except from aficionados of Ryanair!)

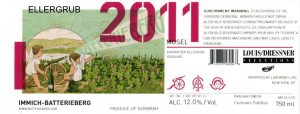

One of Immich-Batterieberg’s single-vineyard Rieslings comes from Steffensberg, a full-south facing site north of Enkirch in the Grossbachtal, a side valley just east of the Mosel, notable for its generous endowment of red slate. This site gives Immich-Batterieberg’s most generous, full-flavored and precocious wine, a combination of red fruit aromas like cassis with juicy stone fruits, with both wrapped around a flinty core. The other sites used for single-vineyard wines are found along the Starkenberger Hang, a steep escarpment between the D53 road along the Mosel’s right bank and the much narrower L192 road that snakes uphill from Enkirch and then to Starkenburg along the ridgetop. Because the Mosel here flows almost perfectly south-to-north, all of these sites are west- or southwest-oriented. Moving south from Enkirch, and skipping Herrenberg, wherein the estate does not farm any parcels, Batterieberg and Zeppwingert come first. Batterieberg is a 1.1 hectare monopole within Zeppwingert, created between 1841 and 1845 when Carl August Immich dynamited an especially intractable part of the hill to make it terrace-able, plant-able and viable as vineyard. Locals nicknamed the hill for his crazy intervention; much the way Alaska became Seward’s Folly, Immich’s new vineyard was dubbed something like “artillery hill” or hill made with explosive charges. In due season, however, Carl August attached the newly-minted Batterieberg name to his own, officially rebaptizing his estate. Finally, south of both Batterieberg and Zeppwingert, the estate also farms parcels in Ellergrub, the southernmost of the Enkircher vineyards, on the escarpment just below Starkenburg. With the exception of Herrenberg, which was redeveloped in the 1970s pursuant to Flurbereinigung, the vineyards along the Starkenberger Hang contain an impressive population of ungrafted vines, some of which date back as far as the end of the 19th Century.

Batterieberg is a grey-slate site loaded with quartz. Perhaps fittingly given its name, it has a reputation for length and power as well as finesse, and for being tightly wound in its youth. Zeppwingert is less rocky than Batterieberg, and the surface soil is darker than Batterieberg’s grey slate. It gives fruit-sweet (but not necessarily sugar-sweet) wines with honeysuckle prominent among various floral properties. Ellergrub, a blue slate site, makes a cool, elegant, and silky wine in which floral elements are often mixed with notes of citrus oil and almonds. Kollmann is especially proud of it; for him it is the estate’s best wine in most vintages.

Dinner with Kollmann was also a good opportunity to fill some gaps in the estate’s recent history. The basic story is clear enough. The estate, which has monastic roots, is mentioned as early as the 10th Century. At the end of the 15th it was purchased by members of the Immich family, whose proprietorship lasted nearly five centuries. Georg Immich, the last Immich to own the estate, sold it in 1989. David Schildknecht, who knew Immich quite well, describes the circumstances surrounding the sale and its aftermath as “a tale of … betrayal, divorce, decline and criminal deceit,” but even observers without Schildknecht’s insight know that the estate’s prevailing style (relatively dry wines fermented with naturally occurring yeast and raised in large oak casks) was turned on its head after the sale, that old oak in the cellar was replaced with stainless steel, that natural yeasts were displaced by exogenous inoculates, and that dry-ish complexity was lost to clean, reductive, fruitiness – from 1992 until the estate went bankrupt in 2007.

It is in 2007 that the stories of Weingut Immich-Batterieberg and Gernot Kollmann intersect. Kollmann is not from winemaking stock, nor a native Moselaner. As a very young man, he imagined a career in medicine. But he was also powerfully interested in wine. In the 1990s he worked at Dr. Loosen. Then he studied viticulture and enology at the Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Wein- und Obstbau at Weinsburg, in Württemberg. Whereupon followed time at the Bischöfliche Weingüter Trier, van Volxem in the Saar, Weingut Jakob Sebastian in the Ahr, and Weingut Knebel at Winningen — of which von Volxem seems to have been the most impactful. When Immich-Batterieberg filed for bankruptcy in 2007, Kollmann saw an opportunity to recapture the estate’s historic distinction – if he could partner with investors. Save for the financial nonsense spawned by the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, which mushroomed into a worldwide recession, swallowing Wall Street banks, Kollmann’s task might have been consummated straightforwardly; in the event potential investors came and went, and Goldman Sachs, Inc., which came to represent the sellers of Immich-Batterieberg, required bailout funds from the American government to remain in business. The investors who worked with Kollmann in 2009 – the Auerbach and Probst families of Hamburg — were successful, however, taking control before the 2009 vintage was harvested. In some ways the delay may have been helpful since it gave Kollmann time to plan carefully for full turnaround bei Immich, which amazed observers and critics when first the 2009 wines, and then subsequent vintages, were released to wildly enthusiastic reviews. The American counter-culture importer Lyle Fass (admittedly given to hyperbole) wrote that Kollmann “shocked the wine world with absolutely one of the greatest wine debuts I have ever encountered;” while David Schildknecht, who is never hyperbolical, reported success “far beyond my skeptical imagination.” (Schildknecht’s observation was made in connection with Kollmann’s decision to use a combination of barrels and stainless tanks in lieu of large Fuder, the latter being unavailable on short notice.) I have no experience with the 2009s, but vintages since 2011 have been stellar, including all the wines (except for one corked bottle) tasted with Kollmann in San Francisco.

Kollmann is a firm believer in the fundamental importance of sites, especially sites enhanced with own-rooted vines, and populated with the grasses and herbs that grow wild even in the rockiest vineyards. And sites in which yields are stringently limited. In the cellar, he works with very little sulfur, which is added only after the wine is essentially made. And yeasts that thrive naturally in the vineyards and cellar, which control fermentations. There are no additions or adjustments to naturally-occuring sugar or acid, and no use of enzymes or colloidal material. This non-interventionist protocol means that fermentations do as they please, giving finished wines with as little as a gram or two of residual sugar, or as much as twelve or seventeen depending on the wine and the vintage, but Kollmann made clear that he is happiest when the wines are truly and completely dry. Across the portfolio, Immich-Batterieberg Rieslings are bright, textured, pure wines, with abundant aromatics, great balance of fruit and structure; sleek, complex and balanced.

In addition to the single-vineyard Rieslings, Immich-Batterieberg makes two blended Rieslings, one called C.A.I. in honor of the aforementioned Carl August Immich, the other Escheburg. The C.A.I. relies on the bottom rows of Batterieberg in combination with purchased grapes; Escheburg is a blend of lots from estate vineyards (see above) that are not used to make the single-vineyard wines. Kollmann also makes some Spätburgunder, but refers to it as a hobby project.

4 January 2018