For a visitor, Marsannay presents today much like other wine communes in the Côte d’Or. The village core is small, covering less surface than a single block in midtown Manhattan. A church and partially shaded benches mark the main place. A modern and generously-appointed municipal complex stands out among older and lesser structures. Signage directs visitors to the cellars of Marsannay’s dozen-plus vignerons, most within a short walk of the village core. The distribution of vineyards is much like other communes too. The best climats are found just upslope of the Route des Grands Crus between the 300 and 400 meter contours, facing predominantly east, and form a nearly continuous ribbon more or less unbroken by fallow land or scrub; lesser sites sit below the Route on flatter and loamier terrain that is shared with other crops and buildings. As elsewhere in the Côte d’Or, Pinot Noir is the sole red tenant in Marsannay’s vineyards, and Chardonnay the main variety among whites.

Marsannay, however, is a special case. It lies just nine kilometers from the Palais des Ducs in Dijon, and barely maintains any degree of separation from Dijon’s seemingly limitless sprawl. Its population has quintupled since 1950, a majority of which is now either retired or works in Dijon, a fact that helps explain the village’s hefty investment in municipal services. The sprawl has also imperiled vineyards, driving Marcenacien vignerons to fight suburbanization, sometimes successfully.

A century ago, however, a different relationship with Dijon changed Marsannay fundamentally, separating its fortunes from the rest of the Côte d’Or and impacting its viticulture in ways that continue to be felt. After mostly prosperous centuries as the capital of the Duchy of Burgundy, and additional centuries of rule by French kings and a regional parlement, Dijon changed vocations after the Revolution. A large urban proletariat replaced erstwhile aristocrats and bureaucrats, creating interalia a new, intense and persistent demand for very ordinary wine. Apparently recognizing an opportunity, Marsannay’s vignerons (and their neighbors at Couchey and Chenôve) uprooted the Pinot Noir that had made the Côte d’Or famous, but yielded parsimoniously, and scrambled to plant more prolific varieties that were well suited to mass market wines, mostly Gamay and Aligoté.

In the 1820s some Marsannay vineyards had figured on lists compiled by André Jullien and Denis Morelot, the first godfathers of vineyard classification in the Côte d’Or. But by 1855 Jules Lavalle, another godfather of the classification, was able to find only a few vineyards anywhere in the Côte Dijonnaise where Pinot was still the main tenant, effectively removing Marsannay and its neighbors from the laborious work that would culminate, by the 1930s, in the ensemble of Burgundy’s controlled appellation arrangements. Phylloxera in the 1870s compounded the impact of the shift to Gamay and Aligoté. Now focused on cheap wine and high margins, Marcenacien vignerons were reluctant to replant after phylloxera struck their vines. Marsannay and its neighbors then missed yet another opportunity to rejoin the mainstream of Côte d’Or activity in the 1920s. Now finally willing to restore Pinot Noir in lieu of Gamay and Aligoté, they dedicated nearly all of their crop to rosé. So it came to pass in the 1930s, when the Burgundian AOCs, including village appellations and cru designations, were created, that no village appellation was approved north of Fixin, nor was any climat north of Fixin accorded cru status.

Today the Marsannay story is all about revival, and quality that is comparable to the rest of the Côte de Nuits. The deep roots of this revival can be traced back to the same to the same “dark” days in the 1920s that has deepened its problems. The bright light was the marriage of one Josef Clair (1889-1971) to Marguerite Daü. Clair replanted Marguerite’s inheritance to eliminate the damage caused by phylloxera, and privileged Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in the process. He also founded Domaine Clair-Daü, the first widely respected estate at Marsannay since the middle of the 19th Century. But the estate’s reputation depended more on its holding outside Marsannay, and most of its replantings of Pinot Noir within the commune went to make rosé.

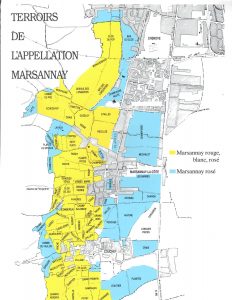

Not until the 1970s and 1980s was there a serious revivial within Marsannay proper, led by a cohort of native sons and exogenous vintners To some degree this cohort was catalyzed by the liquidation of Clair-Daü. The liquidation literally forced Bruno Clair, Josef Clair’s grandson, to set himself up de novo with his part of the sundered estate. Another piece of the estate passed to Monique Bart; this is now the core of Domaine Bart, ably exploited by Monique’s son Martin and nephew Pierre. Other Marcenacien winemakers also rose to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s, notably Sylvain Pataille, Laurent Fournier (Domaine Jean Fournier) and Philippe Huguenot (Huguenot Père et Fils). Signs of seriousness were widespread. Pataille was a trained enologist before creating his estate; Bruno Clair hired a full-time enologist so that he could devote the lion’s share of his personal attention to the vines rather than the cellar. Again there was an elbow effect from the proximity of Marsannay to Dijon: to prevent good vineyard land from falling victim to shopping centers and suburban housing, the Marcenacien vintners were forced to make common cause. The same sense of common cause was then deployed in support of a shift from simple rosé back to serious red wines from historically superior sites. This embrace of red wines as the commune’s crown jewels, and the steady increase in the planted surface devoted to red wine production, were key factors in the INAO’s 1987 approval of a Marsannay AOC including parts of Chenôve and Couchey – enfin.

Now young Marcenacien vintners have launched the commune’s most ambitious quest yet: to secure 1er Cru status for the AOC’s best lieux-dits. With the help of geologists who worked to align geological maps of the area with the boundaries of lieux-dits, a proposal was first agreed locally, then refined in collaboration with regional authorities, and finally sent forward to the national INAO. The current proposal, under discussion in one form or another since ca. 2008, asks 1er Cru status for 14 of 78 lieux-dits within in the AOC.

The northernmost of the 14 sites is the Clos du Roy, which had once belonged to the Dukes of Burgundy but passed to the French crown at the end of the 15th Century. As befits a site named for royalty, Clos du Roy gives especially handsome, elegant wines. The coolest site is said to be Les Echézots, sometimes spelled Es Chezot, which straddles a hill between two combes, basking in downdrafts from both. Echézots gives wines with a somewhat softer elegance than those from Clos du Roy; Echézots’ tannins seem to be wrapped in velvet. The smallest sites are Saint-Jacques and Clos de Jeu, southwest of the village core, and the southernmost is Champ Perdrix, in Couchey. The total surface occupied by the 14 sites amounts to 174 hectares, or roughly 58 percent of the approximately 300 hectares currently approved for the production of red wines within the Marsannay AOC.

Herein lies both ambition and problem. Nearly everyone with responsibility for the reputation of Burgundy’s wines realizes that Marsannay was shortchanged in the 1930s. But vineyard classifications being political as well as scientific, too much change too quickly is not possible. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that, as it stands, the proposal would give Marsannay, in a single stroke, the greatest concentration of 1er Cru Pinot Noir vineyards of any commune in the Côte d’Or which is without Grands Crus. More than neighboring Fixin where 1er Cru vineyards occupy just 19 percent of the surface planted to red grapes. More than Savigny-les-Beaune where the 1er Cru share of the total red surface is 43 percent. Higher even than Nuits-St-Georges, where the analogous number is 45 percent.

Marcenacien vintners being realists, the current bet among them (based on informal conversations I had at this year’s Grands Jours de Bourgogne) is roughly as follows: First, the INAO will approve 1er Cru status for much less than the 174 hectares in the current proposal, probably sometime in the next two or so years. Second, while a few lieux-dits will be approved in their entirety, others will be approved in part only, especially those which are known to contain some land that is too low on the slope or too loamy for top-quality wines. Third, some lieux-dits not approved in whole or in part when the first promotions re announced may still be promoted later. These are bets only. Time will tell.

Although the reclassification saga will likely continue to make headlines, especially when the deed is done, the real story about Marsannay is the persistent increase, year after year, in the number of very good single site wines. Many such wines have already developed enviable reputations. Jérôme Galeyrand has turned heads with his Combe du Pré bottling since 2011. Bruno Clair’s Marsannay flagship, from Les Longeroies, is regarded as sure value-for-money, while his 2014 edition of Les Grasses Têtes, shown at this year’s Grands Jours, was fine and elegant. Also at the Grands Jours, Fougeray de Beauclair’s Les St-Jacques was beautiful and blackberry-inflected; Hervé Charlopin’s 2016 Langerois long and fluid, while Régis Bouvier’s 2016 Longerois was also long but especially rich and velvety.

Despite the press of business associated with the Grands Jours, Martin Bart made time to taste with me in his cellar. Few producers, I would argue, have been more comprehensively serious about their single site wines than Bart. In 2013, the estate, made single site wines from each of nine different lieux-dits: seven climats in Marsannay itself plus Clos du Roy in Chenôve and Champs Salomon in Couchey. Martin does not pretend that all of these are candidates for 1er Cru. Certainly not Les Finottes, a diminutive triangular parcel on nearly flat land composed mostly of deep sand, which gives a lovely, savory and herb-inflected wine that Martin describes as the estate’s “entrée de gamme” among the single site bottlings. It has been made separately since since it became a monopole of the estate simply because it is distinctive, not because it pretends in any way to greatness. It is also worth noting that Domaine Bart cleaves generally to vineyard and cellar practices that showcase the differences among neighboring terroirs. Enlightened farming creates healthier vines in self-sustaining ecosystems. Then, in the cellar, many parameters are terroir-revealing. Sane and appropriate combinations of pre-fermentation cold soaks with fermentation temperatures that begin around 18° C, naturally occurring yeasts, restrained use of pump-overs and pigeage, all help to avoid excessive extraction, which can be terroir-obscuring. The parsimonious use of new oak barrels, rarely more than 25 percent, mixed with older barrels, demi-muids and stainless tanks, helps too, especially for sites in Marsannay which tend generally toward understated, mid-weight wines that open politely but not voluptuously.

When 1er Cru is appended to the names some Marsannay climats in the years ahead, Marcenacien vignerons will have every reason to celebrate. With many of the wines from these lieux-dits already showing praiseworthy excellence, one is perhaps allowed to hope that the new imprimatur, when it comes, will be allowed to lie lightly on Marcenacien labels. Will prices for the newly designated 1er crus rise? Officially, the answer is negative since prices for these wines as site-designated village wine are already higher than village wines without site designations, but in the end supply and demand will rule. On verra.